Difference between revisions of "Pseudoscience"

m (→Overview) |

(typos etc.) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

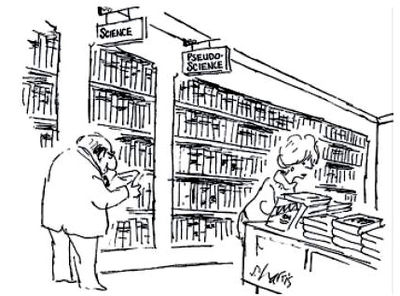

[[image:pseudoscience2.jpg|400px|thumb]] | [[image:pseudoscience2.jpg|400px|thumb]] | ||

| − | '''Pseudoscience''' are theories, beliefs and claims which are presented as scientific but do not adhere to the strict standards of science. They are usually not supported by evidence, not sufficiently tested or even implausible. Scientific terms are often misused or used in a confusing way to resemble real science. Pseudoscientific claims are often not falsifiable and expressed in unclear terms, with the | + | '''Pseudoscience''' are theories, beliefs, and claims which are presented as scientific but do not adhere to the strict standards of science. They are usually not supported by evidence, not sufficiently tested, or even implausible. Scientific terms are often misused or used in a confusing way to resemble real science. Pseudoscientific claims are often not falsifiable and expressed in unclear terms, with the intent to render them difficult to disprove. |

The term "pseudoscience" has been in use since the 18th century and one of the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles". The current definition is more or less based on the works of Thomas Huxley and Karl Popper. Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience<ref>[http://aleph0.clarku.edu/huxley/CE5/S&PS.html T. H. Huxley: Science and Pseudo-Science]</ref><ref>„Incidentally, the philosopher Karl Popper coined the term, ‘pseudo-science’. The examples he gave were (Western) astrology and homeopathy, the medical system developed in Germany.“ V. V. S. Sarma: Natural calamities and pseudoscientific menace. Current Science 90:2 (25. Januar 2006); „The notion of pseudoscience, as coined by philosopher Karl Popper is discussed in the context of its application to library science and its implications for selection.“ Graham Howard: Pseudo Science and Selection. Collection Management 29:2 (24. Mai 2005)</ref> | The term "pseudoscience" has been in use since the 18th century and one of the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles". The current definition is more or less based on the works of Thomas Huxley and Karl Popper. Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience<ref>[http://aleph0.clarku.edu/huxley/CE5/S&PS.html T. H. Huxley: Science and Pseudo-Science]</ref><ref>„Incidentally, the philosopher Karl Popper coined the term, ‘pseudo-science’. The examples he gave were (Western) astrology and homeopathy, the medical system developed in Germany.“ V. V. S. Sarma: Natural calamities and pseudoscientific menace. Current Science 90:2 (25. Januar 2006); „The notion of pseudoscience, as coined by philosopher Karl Popper is discussed in the context of its application to library science and its implications for selection.“ Graham Howard: Pseudo Science and Selection. Collection Management 29:2 (24. Mai 2005)</ref> | ||

==Overview== | ==Overview== | ||

| − | There are several criteria | + | There are several criteria which distinguish science from pseudoscience. Basically, if a scientific claim does not meet scientific norms it may be classified as pseudoscience. Distinguishing between bad or deceptive research in science and pseudoscience is often difficult. One difference is that pseudoscientific claims are often in conflict with empiric scientific knowledge and created specifically to support a certain model of thinking, while fraudulent science tries to fit its "results" into current scientific theories. Scientific jokes and fraud in science are not considered as pesudoscience. |

| − | Pseudoscientific claims are usually created by single persons | + | Pseudoscientific claims are usually created by single persons whose authority must not be doubted. The claims of the creator are to be seen as a dogma and pleaded as such. Experiments and theoretical approaches to explain a phenomenon are always explained or reinterpreted to support the dogma. |

| − | Pseudoscientists often use "experiments" to prove their claims, but manipulate | + | Pseudoscientists often use "experiments" to prove their claims, but manipulate either selection or results to "prove" the alleged validity of their claims.<ref>http://www.xy44.de/belladonna/ Gerhard Bruhn, Erhard Wielandt, Klaus Keck: Pseudowissenschaften an der Universität Leipzig</ref> Often an "[[Inverted Occam's Razor]]" will be applied: A complex and/or absurd theorie is preferred over a simple explanation. Also, pseudoscience never changes and updates its views when new evidence is found. If it can be fitted into the theory, this evidence is embraced and used. If it does not fit, evidence is ignored, dismissed, or claimed to be bogus. |

| − | Esoterics often look | + | Esoterics often look for an extension or improvement of science and end up as enemies of science. |

==Typical Characteristics== | ==Typical Characteristics== | ||

| − | * Claims | + | * Claims are not supported by evidence. These claims will often be in conflict with current experimental data or mathematical theories, and sometimes even contradict common sense. |

| − | * Based on sources | + | * Based on sources which cannot be validated |

| − | * Based on experiments | + | * Based on experiments which cannot be reproduced (or yield different results) |

| − | * | + | * Contradictory [[Occam's Razor]] |

| − | * Systematically ignore evidence or only select | + | * Systematically ignore evidence or only select convenient evidence |

==The seven sins of pseudoscience== | ==The seven sins of pseudoscience== | ||

| − | Several science theoreticians have compiled lists of the sins | + | Several science theoreticians have compiled lists of the sins distinguishing pseudoscience from real science. This includes lists by Langmuir ([1953] 1989), Gruenberger (1964), Dutch (1982), Bunge (1982), Radner and Radner (1982), Kitcher (1982, 30–54), Hansson (1983), Grove (1985), Thagard (1988), Glymour and Stalker (1990), Derkson (1993, 2001), Vollmer (1993), Ruse (1996, 300–306) and Mahner (2007)<ref>[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/pseudo-science/ Science and Pseudo-Science], Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy</ref><ref>Deerksen A.A: ''The seven sins of pseudo-science'', Journal for General Philosophy of Science, Volume 24, Number 1 / März 1993</ref>. These are usually: |

| − | #Belief in authority: It is contended that some person or persons have a special ability to determine what is true or false. Others | + | #Belief in authority: It is contended that some person or persons have a special ability to determine what is true or false. Others must accept their judgments. |

| − | #Nonrepeatable experiments: Reliance is put on experiments that cannot be repeated by others with the same | + | #Nonrepeatable experiments: Reliance is put on experiments that cannot be repeated by others with the same result. |

| − | #Handpicked examples: Handpicked examples are used although they are not representative of the general category | + | #Handpicked examples: Handpicked examples are used although they are not representative of the general category the investigation refers to. |

#Unwillingness to test: A theory is not tested although it is possible to test it. | #Unwillingness to test: A theory is not tested although it is possible to test it. | ||

| − | #Disregard of refuting information: Observations or experiments | + | #Disregard of refuting information: Observations or experiments in conflict with a theory are neglected. |

| − | #Built-in subterfuge: | + | #Built-in subterfuge: Testing of a theory is arranged in such ways that results will always confirm the theory, and never disprove it. |

#Explanations are abandoned without replacement. Tenable explanations are given up without being replaced, so that the new theory leaves much more unexplained than the previous one. (Hansson 1983) | #Explanations are abandoned without replacement. Tenable explanations are given up without being replaced, so that the new theory leaves much more unexplained than the previous one. (Hansson 1983) | ||

<!-- Skipped parascience, seems to be even less used in english than in german --> | <!-- Skipped parascience, seems to be even less used in english than in german --> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Quotes== |

*''In science, the burden of proof falls upon the claimant; and the more extraordinary a claim, the heavier is the burden of proof demanded. The true skeptic takes an agnostic position, one that says the claim is not proved rather than disproved. He asserts that the claimant has not borne the burden of proof and that science must continue to build its cognitive map of reality without incorporating the extraordinary claim as a new "fact." Since the true skeptic does not assert a claim, he has no burden to prove anything. He just goes on using the established theories of "conventional science" as usual. But if a critic asserts that there is evidence for disproof, that he has a negative hypothesis --saying, for instance, that a seeming psi result was actually due to an artifact--he is making a claim and therefore also has to bear a burden of proof [...]''<ref>Marcello Truzzi, On Pseudo-Skepticism</ref> | *''In science, the burden of proof falls upon the claimant; and the more extraordinary a claim, the heavier is the burden of proof demanded. The true skeptic takes an agnostic position, one that says the claim is not proved rather than disproved. He asserts that the claimant has not borne the burden of proof and that science must continue to build its cognitive map of reality without incorporating the extraordinary claim as a new "fact." Since the true skeptic does not assert a claim, he has no burden to prove anything. He just goes on using the established theories of "conventional science" as usual. But if a critic asserts that there is evidence for disproof, that he has a negative hypothesis --saying, for instance, that a seeming psi result was actually due to an artifact--he is making a claim and therefore also has to bear a burden of proof [...]''<ref>Marcello Truzzi, On Pseudo-Skepticism</ref> | ||

Revision as of 14:02, 9 March 2011

Pseudoscience are theories, beliefs, and claims which are presented as scientific but do not adhere to the strict standards of science. They are usually not supported by evidence, not sufficiently tested, or even implausible. Scientific terms are often misused or used in a confusing way to resemble real science. Pseudoscientific claims are often not falsifiable and expressed in unclear terms, with the intent to render them difficult to disprove.

The term "pseudoscience" has been in use since the 18th century and one of the first recorded uses of the word "pseudo-science" was in 1844 in the Northern Journal of Medicine, I 387: "That opposite kind of innovation which pronounces what has been recognized as a branch of science, to have been a pseudo-science, composed merely of so-called facts, connected together by misapprehensions under the disguise of principles". The current definition is more or less based on the works of Thomas Huxley and Karl Popper. Popper proposed falsifiability as an important criterion in distinguishing science from pseudoscience[1][2]

Overview

There are several criteria which distinguish science from pseudoscience. Basically, if a scientific claim does not meet scientific norms it may be classified as pseudoscience. Distinguishing between bad or deceptive research in science and pseudoscience is often difficult. One difference is that pseudoscientific claims are often in conflict with empiric scientific knowledge and created specifically to support a certain model of thinking, while fraudulent science tries to fit its "results" into current scientific theories. Scientific jokes and fraud in science are not considered as pesudoscience.

Pseudoscientific claims are usually created by single persons whose authority must not be doubted. The claims of the creator are to be seen as a dogma and pleaded as such. Experiments and theoretical approaches to explain a phenomenon are always explained or reinterpreted to support the dogma.

Pseudoscientists often use "experiments" to prove their claims, but manipulate either selection or results to "prove" the alleged validity of their claims.[3] Often an "Inverted Occam's Razor" will be applied: A complex and/or absurd theorie is preferred over a simple explanation. Also, pseudoscience never changes and updates its views when new evidence is found. If it can be fitted into the theory, this evidence is embraced and used. If it does not fit, evidence is ignored, dismissed, or claimed to be bogus.

Esoterics often look for an extension or improvement of science and end up as enemies of science.

Typical Characteristics

- Claims are not supported by evidence. These claims will often be in conflict with current experimental data or mathematical theories, and sometimes even contradict common sense.

- Based on sources which cannot be validated

- Based on experiments which cannot be reproduced (or yield different results)

- Contradictory Occam's Razor

- Systematically ignore evidence or only select convenient evidence

The seven sins of pseudoscience

Several science theoreticians have compiled lists of the sins distinguishing pseudoscience from real science. This includes lists by Langmuir ([1953] 1989), Gruenberger (1964), Dutch (1982), Bunge (1982), Radner and Radner (1982), Kitcher (1982, 30–54), Hansson (1983), Grove (1985), Thagard (1988), Glymour and Stalker (1990), Derkson (1993, 2001), Vollmer (1993), Ruse (1996, 300–306) and Mahner (2007)[4][5]. These are usually:

- Belief in authority: It is contended that some person or persons have a special ability to determine what is true or false. Others must accept their judgments.

- Nonrepeatable experiments: Reliance is put on experiments that cannot be repeated by others with the same result.

- Handpicked examples: Handpicked examples are used although they are not representative of the general category the investigation refers to.

- Unwillingness to test: A theory is not tested although it is possible to test it.

- Disregard of refuting information: Observations or experiments in conflict with a theory are neglected.

- Built-in subterfuge: Testing of a theory is arranged in such ways that results will always confirm the theory, and never disprove it.

- Explanations are abandoned without replacement. Tenable explanations are given up without being replaced, so that the new theory leaves much more unexplained than the previous one. (Hansson 1983)

Quotes

- In science, the burden of proof falls upon the claimant; and the more extraordinary a claim, the heavier is the burden of proof demanded. The true skeptic takes an agnostic position, one that says the claim is not proved rather than disproved. He asserts that the claimant has not borne the burden of proof and that science must continue to build its cognitive map of reality without incorporating the extraordinary claim as a new "fact." Since the true skeptic does not assert a claim, he has no burden to prove anything. He just goes on using the established theories of "conventional science" as usual. But if a critic asserts that there is evidence for disproof, that he has a negative hypothesis --saying, for instance, that a seeming psi result was actually due to an artifact--he is making a claim and therefore also has to bear a burden of proof [...][6]

Literatur

German:

- Alan Sokal, Jean Bricmont (1999): Eleganter Unsinn. Wie die Denker der Postmoderne die Wissenschaften missbrauchen, Muenchen

- Alexander K. Dewdney (1998): Alles fauler Zauber? IQ-Tests, Psychoanalyse und andere umstrittene Theorien, Basel

- Andreas Hergovich (2001): Der Glaube an Psi - Die Psychologie paranormaler Überzeugungen. Bern

- Ben Goldacre: Die Wissenschaftslüge: Wie uns Pseudo-Wissenschaftler das Leben schwer machen. Fischer Frankfurt 2010, ISBN 978-3596185108

- Bernd Harder: Geister, Gothics, Gabelbieger. 66 Antworten auf Fragwürdiges aus Esoterik und Okkultismus. Aschaffenburg: Alibri 2005

- Carl Sagan: Der Drache in meiner Garage. Oder: Die Kunst der Wissenschaft, Unsinn zu entlarven. München: Droemer Knaur 1997

- Christoph Bördlein (2002): Das sockenfressende Monster in der Waschmaschine - Eine Einfuehrung in das skeptische Denken, Aschaffenburg

- Colin Goldner (2000): Die Psycho-Szene

- Douglas R. Hofstadter: Wissenschaft und Aberglaube: ein Kampf zwischen David und Goliath. Spektrum der Wissenschaft April 1982, 8-13

- Gerald L. Eberlein (Hrsg.): Schulwissenschaft – Parawissenschaft – Pseudowissenschaft. Stuttgart: Hirzel 1991

- Gerhard Vollmer: Wozu Pseudowissenschaften gut sind. Argumente aus Wissenschaftstheorie und Wissenschaftspraxis. Universitas 47 (Feb. 1992) 155-168

- Gerhardt Vollmer (1993): Wissenschaftstheorie im Einsatz - Beitraege zu einer selbstkritischen Wissenschaftsphilosophie, Stuttgart

- Gero von Randow (Hrsg.): Der Fremdling im Glas und weitere Anlaesse zur Skepsis, entdeckt im Skeptical Inquirer, Rowohlt, Reinbek, 1996

- Gero von Randow: Mein paranormales Fahrrad – und andere Anlässe zur Skepsis, entdeckt im Skeptical Inquirer. Rowohlt (rororo), Reinbek, 1993

- Hans-Peter Beck-Bornholdt, Hans-Hermann Dubben (1997): Der Hund, der Eier legt - Erkennen von Fehlinformationen durch Querdenken, Reinbek

- Hansjoerg Hemminger, Bernd Harder (2000): Was ist Aberglaube? Bedeutung, Erscheinungsformen, Beratungshilfen, Gütersloh

- Ingo Kugenbuch: Warum sich der Löffel biegt und die Madonna weint - Übersinnliche Phänomene und ihre irdischen Erklärungen. Humboldt Verlag August 2008

- Irmgard Oepen, Amardeo Sarma (Hrsg.) (1995): Parawissenschaften unter der Lupe, Muenster

- Irmgard Oepen, Krista Federspiel, Amardeo Sarma (Hrsg.) (1999): Lexikon der Parawissenschaften - Astrologie, Esoterik, Okkultismus, Paramedizin, Parapsychologie kritisch betrachtet, Muenster

- James Randi (2001): Lexikon der Übersinnlichen Phänomene - Die Wahrheit über die paranormale Welt, Muenchen

- Joachim Herrmann: Das falsche Weltbild. Astronomie und Aberglaube. Stuttgart: Franckh 1962; dtv 958, 1973

- M. Ecker: Kritisch argumentieren. Aschaffenburg: Alibri 2006

- Marcello Truzzi: Überlegungen zur Kontroverse um Wissenschaft und Pseudowissenschaft. In: H.P. Duerr (Hrsg.): Der Wissenschaftler und das Irrationale. Frankfurt: Syndikat 1985, Band IV, 48-63

- Markus Poessel (2000): Phantastische Wissenschaften - über Erich von Daeniken und Johannes von Buttlar, Reinbek

- Michael Shermer, Benno Maidhof-Christig, Lee Traynor (1998): Endzeittaumel - Propheten, Prognosen, Propaganda, Aschaffenburg

- Otto Prokop, Wolf Wimmer (1987): Der moderne Okkultismus, Stuttgart

- Stuart A. Vyse (1999): Die Psychologie des Aberglaubens - Schwarze Kater und Maskottchen, Basel

- Time-Life: Irrwege der Wissenschaft. Amsterdam 1993

- Wolfgang Hell, Klaus Fiedler, Gerd Gigerenzer (Hrsg.) (1993): Kognitive Taeuschungen - Fehl-Leistungen und Mechanismen des Urteilens, Denkens und Erinnerns, Heidelberg

- Wolfgang Hund (2000): Falsche Geister - echte Schwindler? Esoterik und Okkultismus kritisch hinterfragt, Wuerzburg

- Harald Wiesendanger: Zwischen Wissenschaft und Aberglaube. Grenzbereiche psychologischer Forschung. Frankfurt: Fischer-TB 42326, 1989

English:

- A. Lugg: Bunkum, flim-flam and quackery: pseudoscience as a philosophical problem. Dialectica 41 (1987) 221-230

- Anton Derksen: The seven sins of pseudoscience. Journal for General Philosophy of Science 24 (1993) 17-42

- Ben Goldacre: Bad Science: Quacks, Hacks, and Big Pharma Flacks, Faber & Faber Reprint 2010, ISBN 978-0865479180

- Carl Sagan: The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, Ballantine Books 1997, ISBN 978-0345409461

- G. Bakker, L. Clark: Explanation. An introduction to the philosophy of science. Mountain View (Ca.): Mayfield 1988

- Imre Lakatos: Science and pseudoscience. Conceptus 8, Nr. 24 (1974) 5-9

- James Randi (1995): Flim-Flam - Psychics, ESP, Unicorns and other Delusions, New York

- James Randi: An Encyclopedia of Claims, Frauds, and Hoaxes of the Occult and Supernatural, St. Martin's Griffin 1997, ISBN 978-0312151195

- James Randi: Flim-Flam! Buffalo: Prometheus 1982

- Kenneth L. Feder: Frauds, Myth, and Mysteries - Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, 2001

- M.A. Rothman: A physicist’s guide to skepticism. Applying laws of physics to faster-than-light travel, psychic phenomena, telepathy, time travel, UFO’s, and other pseudoscientific claims. Buffalo: Prometheus 1988

- Mario Bunge: Scientific research. New York: Springer 1967, vol. I, 36-44

- Martin Gardner (1957): Fads &; Fallacies - In the Name of Science, New York

- Michael Scriven: The frontiers of psychology: psychoanalysis and parapsychology. In: R.G. Colodny Frontiers of science and philosophy. Lanham: University Press of America 1983, 79-129

- Michael Shermer, Pat Linse (2002): The Skeptic Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience

- Michael Shermer: (1998): Why people believe in weird things - pseudoscience, superstition, and other confusions of our time, New York

- Patrick Grim (ed.): Philosophy of science and the occult. Albany: State University of New York Press 1982, 1990

- Paul Kurtz (1992): The New Skepticism: Inquiry and Reliable Knowledge

- Paul Kurtz (2001): Skeptical Odysseys: Personal Accounts by the World's Leading Paranormal Investigation

- Philip Plait: Bad Astronomy - Misconceptions and Misuses Revealed, from Astrology to the Moon Landing "Hoax", New York 2002

- Terence Hines: Pseudoscience and the paranormal. A critical examination of the evidence. Buffalo: Prometheus

- Theodore Schick Jr., Lewis Vaughn (2004): How to think about weird things - critical thinking for a New Age

Weblinks

- Wikipedia about Pseudoscience

- Website of James Randi

- Website of Ben Goldacre

- SCIgen - An Automatic CS Paper Generator

- Blog of Edzard Ernst

- http://home.tele2.at/aloisreutterer/wissenschaft.htm (German)

- http://www.wort-und-wissen.de/index2.php?artikel=sij/sij72/sij72-3.html (German)

- http://members.fortunecity.com/lange42/pseudo.htm (German)

Versions of this article in other languages

- deutsch: Pseudowissenschaft

Quellennachweise

- ↑ T. H. Huxley: Science and Pseudo-Science

- ↑ „Incidentally, the philosopher Karl Popper coined the term, ‘pseudo-science’. The examples he gave were (Western) astrology and homeopathy, the medical system developed in Germany.“ V. V. S. Sarma: Natural calamities and pseudoscientific menace. Current Science 90:2 (25. Januar 2006); „The notion of pseudoscience, as coined by philosopher Karl Popper is discussed in the context of its application to library science and its implications for selection.“ Graham Howard: Pseudo Science and Selection. Collection Management 29:2 (24. Mai 2005)

- ↑ http://www.xy44.de/belladonna/ Gerhard Bruhn, Erhard Wielandt, Klaus Keck: Pseudowissenschaften an der Universität Leipzig

- ↑ Science and Pseudo-Science, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ↑ Deerksen A.A: The seven sins of pseudo-science, Journal for General Philosophy of Science, Volume 24, Number 1 / März 1993

- ↑ Marcello Truzzi, On Pseudo-Skepticism