Difference between revisions of "Éliphas Lévi"

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[image:Eliphas_Levi_1874.jpg|Alphonse-Louis Constant, alias Éliphas Lévi in 1874|thumb]]'''Éliphas Lévi''', also '''Éliphas Lévi Zahed''' was the pseudonym under which from 1854 on the catholic cleric '''Alphonse-Louis Constant''' (February 8, 1810, Paris - May 31, 1875, ibid.) wrote and published scriptures of occult and magical contents. Lévi is said to have been the re-founder of occultism in the 19th century. | + | [[image:Eliphas_Levi_1874.jpg|Alphonse-Louis Constant, alias Éliphas Lévi in 1874|thumb]]'''Éliphas Lévi''', also '''Éliphas Lévi Zahed''' was the pseudonym under which from 1854 on the catholic cleric '''Alphonse-Louis Constant''' (February 8, 1810, Paris - May 31, 1875, ibid.) wrote and published scriptures of occult and magical contents. Lévi is said to have been the re-founder of occultism in the 19th century.<ref>This article is based on the corresponding item in the French Wikipedia (http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Éliphas_Lévi). Which unfortunately has the disadvantage of lacking references, hence here to they are rather scarce. Presumably the French article is drawn from this source: ''l'Estoile, Arnaud de: ''Qui suis-je? Éliphas Lévi.'' Grez-sur-Loing: Pardès, 2008''. Whenever and wherever necessary and possible the information in the present article have been verified and re-examined.</ref> |

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

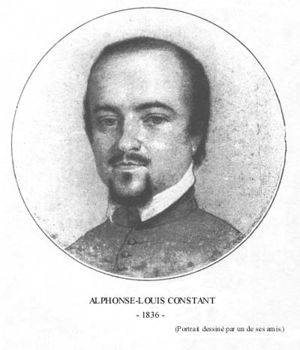

[[image:Eliphas_Levi_1836.jpg|left|Portrait of the young man, 1836|thumb]]Overcome with disappointment when he quit his education, his mother took her life a few weeks later. For Alphonse there commenced a time of aimless searching. Within just one year he made the acquaintance of Honoré de Balzac, developed his gifts of visual arts by collaborating on the chorus line "Les Belles Femmes de Paris", made friends with the militant socialist [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flora_Tristan Flora Tristan], and yet at the same time he carried on dreaming of a future as a priest. This dream guided his way to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter's_Abbey,_Solesmes St. Peter's Abbey], a Benedictine monastery whose library of 20,000 volumes gave him the chance of making himself acquainted with scriptures from the early Christianity, by ancient gnostics, and by religious mystics as well. It was here that he authored a first booklet of his own entitled "Le Rosier de Mai" which was as pious as romantic, and rhapsodized about matters of love in so romantic and vivid a way that it was deemed better to expell him from the monastery. | [[image:Eliphas_Levi_1836.jpg|left|Portrait of the young man, 1836|thumb]]Overcome with disappointment when he quit his education, his mother took her life a few weeks later. For Alphonse there commenced a time of aimless searching. Within just one year he made the acquaintance of Honoré de Balzac, developed his gifts of visual arts by collaborating on the chorus line "Les Belles Femmes de Paris", made friends with the militant socialist [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flora_Tristan Flora Tristan], and yet at the same time he carried on dreaming of a future as a priest. This dream guided his way to [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Peter's_Abbey,_Solesmes St. Peter's Abbey], a Benedictine monastery whose library of 20,000 volumes gave him the chance of making himself acquainted with scriptures from the early Christianity, by ancient gnostics, and by religious mystics as well. It was here that he authored a first booklet of his own entitled "Le Rosier de Mai" which was as pious as romantic, and rhapsodized about matters of love in so romantic and vivid a way that it was deemed better to expell him from the monastery. | ||

| − | Following an intervention in his support by the archbishop of Paris, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denis_Auguste_Affre Denis Auguste Affre], Constant finally was given an appointment as warden at the college of Juilly, east of Paris. However, his seniors treated him badly, but now all the wrath broke out of him, and he wrote a first raging pamphlet, ''La Bible de la liberté''. With its publication in February 1841 he not only provided for a outright scandal throughout the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but at the court in Versailles as well<ref>There exists a rather sardonic narration of these incidents and of the following | + | Following an intervention in his support by the archbishop of Paris, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denis_Auguste_Affre Denis Auguste Affre], Constant finally was given an appointment as warden at the college of Juilly, east of Paris. However, his seniors treated him badly, but now all the wrath broke out of him, and he wrote a first raging pamphlet, ''La Bible de la liberté''. With its publication in February 1841 he not only provided for a outright scandal throughout the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but at the court in Versailles as well<ref>There exists a rather sardonic, but contemporary narration of these incidents and of the following: [http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb33497059p Mystères galans des théâtres de Paris]. Paris: Cazel, 1844. Page 88 et seq.</ref>. He was arrested, and sentenced in May 1841 to eight months of imprisonment, with an additional fine of 300 Francs. Since he couldn't afford the money he served eleven months, a time which he used for studying the works of the Swedish mystic [[Emmanuel Swedenborg]]. |

| − | After Constant's discharge bishop Affre recommended him to his colleague in Evreux, where from February 1843 on he preached in so successful a way that his fellow ministers jealously announced the death of abbé Constant in the newspapers. Despite a swift denial another scandal couldn't be avoided, however, the bishop kept his hand upon him, and commissioned him with the realisation of a mural painting in a nunnery. At about the same time he nearly became a member of the secretive [[Rosicrucianism|Rosicrucian Order]]. Friends of his father's vouched for him, by which he might even have prospects of the rank of a Grand Master. Unfortunately nothing of that came about, and the painting too would not be finished | + | After Constant's discharge bishop Affre recommended him to his colleague in Evreux, where from February 1843 on he preached in so successful a way that his fellow ministers jealously announced the death of abbé Constant in the newspapers. Despite a swift denial another scandal couldn't be avoided, however, the bishop kept his hand upon him, and commissioned him with the realisation of a mural painting in a nunnery. At about the same time he nearly became a member of the secretive [[Rosicrucianism|Rosicrucian Order]]. Friends of his father's vouched for him, by which he might even have prospects of the rank of a Grand Master. Unfortunately nothing of that came about, and the painting too would not be finished. Because when in 1844 his second sweeping blow appeared, ''La Mère de Dieu'', his relationship with the bishop experienced a rapid deterioration, and Constant returned to Paris. |

| − | Being deeply churned up by the death of his friend Flora Tristan he published ''L'Émancipation de la femme ou le Testament de la paria'', followed a year later (1845) by his pacifist manifesto ''La Fête-Dieu ou le Triomphe de la paix religieuse''. After all, he occupied himself busily with the humanistic, and the utopian ideas of the time, particularly [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Simonianism Saint-Simonianism] and the theories of [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_fourier Charles Fourier]. Neither of them could convince him: Saint Simon teaches religion without religiousness, which he found repulsive. And Fourier's approach of man's necessity for acting out his drives he considered absurd and foolish. He was 35 now, and still | + | Being deeply churned up by the death of his friend Flora Tristan he published ''L'Émancipation de la femme ou le Testament de la paria'', followed a year later (1845) by his pacifist manifesto ''La Fête-Dieu ou le Triomphe de la paix religieuse''. After all, he occupied himself busily with the humanistic, and the utopian ideas of the time, particularly [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saint-Simonianism Saint-Simonianism] and the theories of [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_fourier Charles Fourier]. Neither of them could convince him: Saint Simon teaches religion without religiousness, which he found repulsive. And Fourier's approach of man's necessity for acting out his drives he considered absurd and foolish. He was 35 now, and still his search continued. |

Revision as of 06:42, 7 September 2011

Éliphas Lévi, also Éliphas Lévi Zahed was the pseudonym under which from 1854 on the catholic cleric Alphonse-Louis Constant (February 8, 1810, Paris - May 31, 1875, ibid.) wrote and published scriptures of occult and magical contents. Lévi is said to have been the re-founder of occultism in the 19th century.[1]

Life

Per aspera ...

Alphonse-Louis's father was a shoemaker living in what is today the 6th Arrondissement in Paris, on the left bank of the Seine. The family's material conditions were very limited, but the parson at the church of Saint-André-des-Arts was running a school free of charge for the poor, at which Alphonse-Louis too would receive basic education. After that, and several intermediary steps later, last of which the seminary of Saint-Sulpice, in 1835 he became ordained sub-deacon, and from then on he was himself entrusted with teaching appointments. With one of his schoolgirls (whom in his confusion he took for a reincarnation of Virgin Mary) he fell in immortal love, and left the seminary for her just before he was to be ordained priest. But alas, she ran out on him.

Overcome with disappointment when he quit his education, his mother took her life a few weeks later. For Alphonse there commenced a time of aimless searching. Within just one year he made the acquaintance of Honoré de Balzac, developed his gifts of visual arts by collaborating on the chorus line "Les Belles Femmes de Paris", made friends with the militant socialist Flora Tristan, and yet at the same time he carried on dreaming of a future as a priest. This dream guided his way to St. Peter's Abbey, a Benedictine monastery whose library of 20,000 volumes gave him the chance of making himself acquainted with scriptures from the early Christianity, by ancient gnostics, and by religious mystics as well. It was here that he authored a first booklet of his own entitled "Le Rosier de Mai" which was as pious as romantic, and rhapsodized about matters of love in so romantic and vivid a way that it was deemed better to expell him from the monastery.

Following an intervention in his support by the archbishop of Paris, Denis Auguste Affre, Constant finally was given an appointment as warden at the college of Juilly, east of Paris. However, his seniors treated him badly, but now all the wrath broke out of him, and he wrote a first raging pamphlet, La Bible de la liberté. With its publication in February 1841 he not only provided for a outright scandal throughout the ecclesiastical hierarchy, but at the court in Versailles as well[2]. He was arrested, and sentenced in May 1841 to eight months of imprisonment, with an additional fine of 300 Francs. Since he couldn't afford the money he served eleven months, a time which he used for studying the works of the Swedish mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg.

After Constant's discharge bishop Affre recommended him to his colleague in Evreux, where from February 1843 on he preached in so successful a way that his fellow ministers jealously announced the death of abbé Constant in the newspapers. Despite a swift denial another scandal couldn't be avoided, however, the bishop kept his hand upon him, and commissioned him with the realisation of a mural painting in a nunnery. At about the same time he nearly became a member of the secretive Rosicrucian Order. Friends of his father's vouched for him, by which he might even have prospects of the rank of a Grand Master. Unfortunately nothing of that came about, and the painting too would not be finished. Because when in 1844 his second sweeping blow appeared, La Mère de Dieu, his relationship with the bishop experienced a rapid deterioration, and Constant returned to Paris.

Being deeply churned up by the death of his friend Flora Tristan he published L'Émancipation de la femme ou le Testament de la paria, followed a year later (1845) by his pacifist manifesto La Fête-Dieu ou le Triomphe de la paix religieuse. After all, he occupied himself busily with the humanistic, and the utopian ideas of the time, particularly Saint-Simonianism and the theories of [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_fourier Charles Fourier]. Neither of them could convince him: Saint Simon teaches religion without religiousness, which he found repulsive. And Fourier's approach of man's necessity for acting out his drives he considered absurd and foolish. He was 35 now, and still his search continued.

References

- ↑ This article is based on the corresponding item in the French Wikipedia (http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Éliphas_Lévi). Which unfortunately has the disadvantage of lacking references, hence here to they are rather scarce. Presumably the French article is drawn from this source: l'Estoile, Arnaud de: Qui suis-je? Éliphas Lévi. Grez-sur-Loing: Pardès, 2008. Whenever and wherever necessary and possible the information in the present article have been verified and re-examined.

- ↑ There exists a rather sardonic, but contemporary narration of these incidents and of the following: Mystères galans des théâtres de Paris. Paris: Cazel, 1844. Page 88 et seq.